Common algorithmization makes the user of several booking platforms (OTA – online travel agencies) feel that the available tools, instead of serving him/her, are rather intended to discipline him/her into specific behaviour (‘expectations’ of algorithms). The question is how to make use of technological competencies to turn the buyer’s journey into a fascinating experience, not a torment.

Let’s ask the consumers

In search for an answer, Amadeus commissioned PhoCusWright[1] to conduct a study to establish:

(1) how consumers make travel decisions,

(2) how far in advance they plan their trips,

(3) how they book, and finally

(4) how they would like to make such decisions in the future.

The survey covered only those respondents who declared their intention to participate in discretionary travels. The term ‘discretionary trip’ refers to a trip taken to a destination that was chosen independently by the respondent, as opposed to trips that have a pre-determined destination like business trips or visits with friends/family.

The test mode used should be explained in two ways:

- firstly, determining how tourists plan their trips required the exclusion of people who had a pre-imposed purpose and date of departure

- secondly, recognizing how respondents envision their FUTURE tourist purchases.

Who was examined and how?

The survey looked at adults (≥18 years old) in the US, UK, Germany, India, Russia, and Brazil, which ensured geographic and cultural diversity and provided information on the online navigation pattern of consumers from such diverse areas. To qualify for participation in the study, respondents had to indicate they had taken at least three overnight trips in the past 12 months that included paid lodging, air travel, and/or long-distance rail travel. At least one of these trips had to be a discretionary trip. Respondents were also required to have played an active role in planning these trips. Ultimately, 4638 questionnaires were included in the study.

The summer journey begins in winter…

The experts reached for the opinions of trendsetters who are eager to pick up technological innovations and are also eager to share information with their friends. The way they function in the world of new technologies is reflected in the way they travel: they choose their travel destinations on their own, they like to discover new destinations, they are not afraid of costs, but they want to be sure that money will provide them with an unforgettable experience. They consider the planning stage of the trip to be part of the tourist experience: their final opinion about a vacation brings together planning, shopping, and the trip itself.

Vacation planning often begins a few months before the actual date of departure, and the experiences from the stage of searching for inspiration are combined with the experiences of the trip itself. The frequency of travel, which in the case of trendsetters is very high, makes them experienced planners: they go through this process so often that they can formulate bold objections as to its course, indicate irritating or time-consuming (and often unnecessary) stages, and finally present expectations as to possible improvements and the shortcomings in the available travel planning tools.

Before an accusation is made that the behaviour of trendsetters does not reflect the general behaviour of tourists, it is worth emphasizing that when thinking about innovations, one cannot be guided by what is happening on the mass market (I had a similar argument when I presented the results of the research conducted among Polish students). In both cases we are dealing with young people (under 34 years of age), tech-savvy, open to new experiences. Undoubtedly, this is not a mass tourist, but a tourist of the future: at the age of 50 and over, these people will still reach for technological solutions and continue to be critical of them. The availability of data in the hands of online agencies should encourage them to create intelligent ecosystems to support stakeholders: both consumers and tourism service providers, rather than stay complacent with what is offered to mass buyers today.

What do we know about on-line tourist shopping?

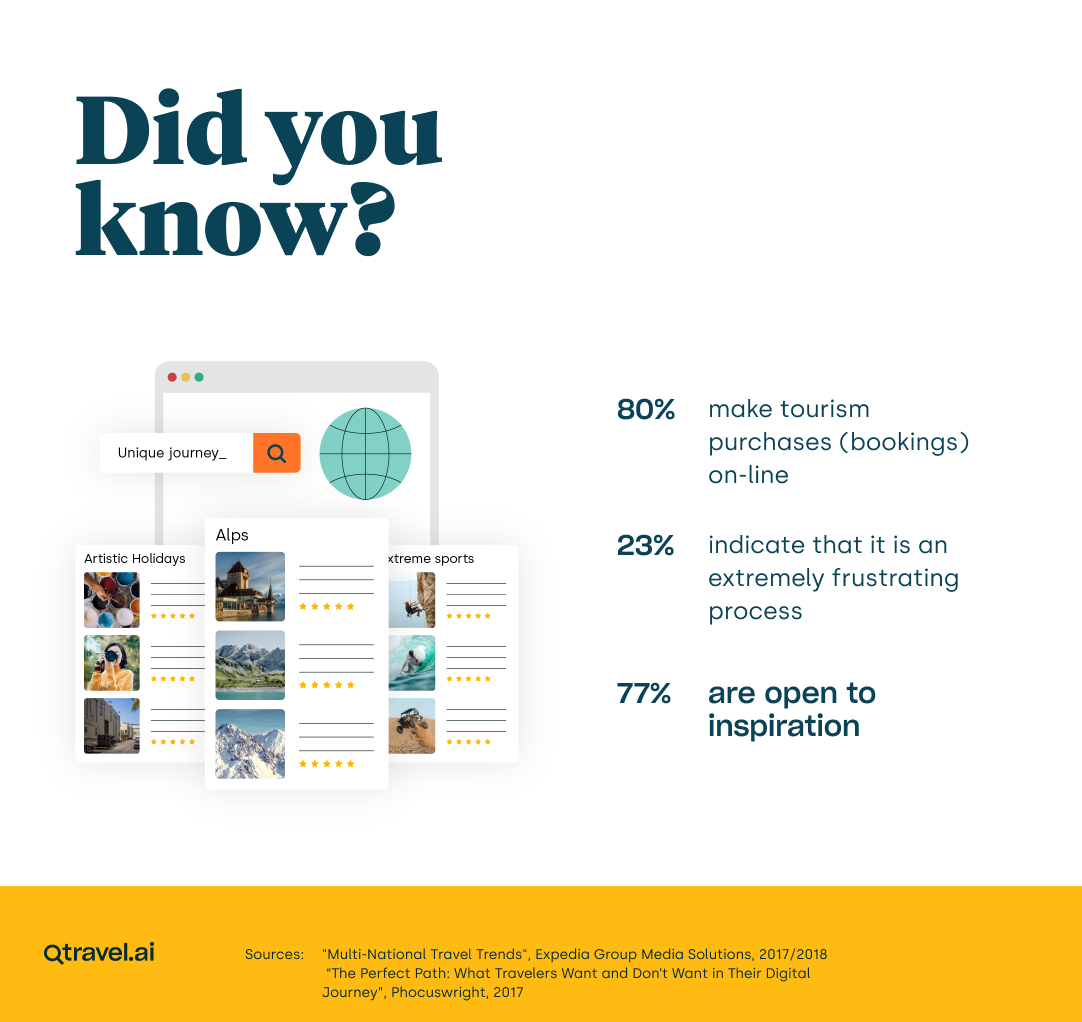

According to the PhoCus Wright survey results [1], 80% of respondents make tourism purchases (bookings) on-line and look for information and inspiration there as well (it is worth adding that 100% of tourists make any travel-related activities online – for example searching for information about opening hours of facilities). However, as many as 23% of them indicate that it is an extremely frustrating process, owing to the large amount of time required, information overload, surprising price changes, and the lack of appropriate visualization (photos or videos). The respondents are also displeased with an insufficient range of photographs (e.g. photos are taken only inside the facility, or only during the day, so one can see the interior of the restaurant, but cannot find a view from the window offered in a given room). Similar research carried out in Poland showed that the lack of photos or their insufficient range prompts as many as 76% of users to immediately leave the website and look for another source of information. On the other hand, the factor that makes them return to a given website is its intuitiveness and ease of navigation.

Maybe it’s better to visit a traditional travel agency?

According to Phocuswright, there are usually two factors that drive buyers to seek traditional support:

- looking for a personalized service

- insufficient information available on the website.

But beware: what tourists refer to as ‘information scarcity’ is in fact an excess of irrelevant content, its bad organization, and difficult navigation. Inundated with an excess of unstructured content, the user gets discouraged. His expectations can be formulated as follows: “first the basic search results correspond to a general, but personalized, expectation, then the ability to drill down into more detail”. One of the British tourists who persistently resisted the algorithmization I wrote about recently, gave the following opinion: “Not possible to use my precise search criteria – have to start with destination and date, though there are other aspects that are much more important to me. If I could do a fully tailored search, I would be delighted”[2].

Another issue is the responsiveness of websites and the growing importance of mobile devices, both in the process of vacation planning and booking (as much as 65% of responses in the US). When making a reservation from a mobile device, tourists prefer to use the application or website of a specific travel agency or airline, but when using stationary devices – they prefer internet search engines. In any case, the annoyance may be caused by too many steps to complete online payment[1].

Search criteria as a digital Achilles heel

It would be easy to run an online tourist business if the tourists always reported what they wanted. But with the development of the Internet, a group of consumers has emerged who start planning holidays by looking for inspiration: they do not know where they want to go, at what time of the year, with whom, or even why. They are open to new ideas and will gladly adjust the date of departure to those ideas, as long as the inspiration is really strong and suggestive, fully adapted to their behavioural profile.

Trendsetters especially appreciate the possibility of acquiring new skills and impressions. I have never ridden a horse? I have never been paragliding? I have never dived? Well, it’s time to make up for it! The stimulus does not have to be the activity itself, but also its effects. For example, a photo of a coral reef on Instagram – if I want to do the same, I have no choice but to go to the right place and learn certain skills.

When it comes to sources of tourist inspiration – the responses of respondents from the surveyed countries[1] do not differ much from the opinions of Polish students: online reviews, opinions, and photos posted by friends on social media, promotional materials of tourist organizations and regions, and YouTube videos. The most important role is played by visual media (especially in the 18-34 age group) supported by social relations (the possibility to consult friends).

According to the respondents, one of the factors that weaken their willingness to make a purchase is the lack of information on additional services (e.g. clubs, interesting restaurants, markets, etc.). I wonder what algorithm can handle the phrase: “babysitting and swimming pool, dog, horses, culinary workshops, local products, perfumes, lots of fruit.” I will add right away that the respondent who formulated such a query finally found a suitable stay in Provence, threw the children into the swimming pool, sent her husband with friends to a horse rally, and she herself took part in cosmetic workshops, which she alternated with morning shopping in local markets and culinary workshops with famous chefs from all over Europe. Finding the offer took her ‘merely’ 7 months, and required arranging independent transport. The whole process had to be carried out ‘manually’, because neither the date of departure, the number of participants, nor the price of the stay were the key elements of the search and the existing tools did not process such a complex order.

Price or cost – what is the tourist paying for?

There is the problematic issue of tourists’ attitude to prices in all studies. Travel service providers claim that price is a key factor of choice (especially for a Polish buyer), and they go so far as to lure consumers with an attractive price offer. The result is the non-transparency of the offers presented, the omission of many components that will ultimately burden the tourist anyway, and surprising customers at the last minute with expenses that were not included in the budget for the trip. On the other hand, the fashion for smart shopping and the pressure to be a smart consumer make even wealthy customers afraid of overpaying. This is not related to the condition of their wallets, but to the feeling that they ‘got cheated’ because the trip could have been organized more cheaply.

The key to understanding this puzzle is to distinguish the price from the total cost to the buyer. The cost includes the time wasted searching the Internet, the frustration of persistently comparing offers that are virtually impossible to compare, phone calls and emails to agencies which are meant to minimize the risk of surprising negative information provided two days before departure. Also frustrating is the inability to compare current prices. Considering that the customer’s shopping path lasts (according to various studies) from several days to over 3 months, in such a long period one should take into account multiple changes in prices. Tourist events that consist of numerous components are difficult to compare, because different tour operators provide information about the factors influencing the final price of the event with varying accuracy. To the financial and time costs, psychologists also add the social cost (my image in the eyes of others) and the psychological cost (my self-esteem). Being ‘not smart enough’ violates these two dimensions: the fact that friends spent a similar vacation for a lower price, or the awareness that the agent, despite repeated requests, omitted key information, is perceived by the consumer as a violation of his own dignity.

However, it is worth remembering that affluent tourists are increasingly aware of the total cost of organizing holiday trips, which results from the fact that better off people are more aware of the value of a unit of free time. The more expensive the hour of my life is, the more I care about its quality and the more likely I will find a professional who will relieve me of the tedious search of offers. If this professional is available 24/7 and can take into account the most important criteria for my trip – there is a good chance that he will gain my loyalty. Therefore, we should strive to ensure that digital solutions dedicated to planning and booking tourist trips are as professional as a traditional agent, but as available day and night as the Internet. This combination is intended to be offered by digital tools based on natural language understanding.